As I prepare to conclude my studies in the Ed.S. Instructional Technology program at the University of Montevallo, I am submitting my Observer-Participant-Leader (O-P-L) record. This document chronicles activities I completed while enrolled in courses in the program and working as an Instructional Technology Specialist with Homewood City Schools. This blog post reflects on three key activities from my O-P-L record and their connection to the Certified Education Technology Leader (CETL) Framework of Essential Skills.

PLC Book Study Presentation

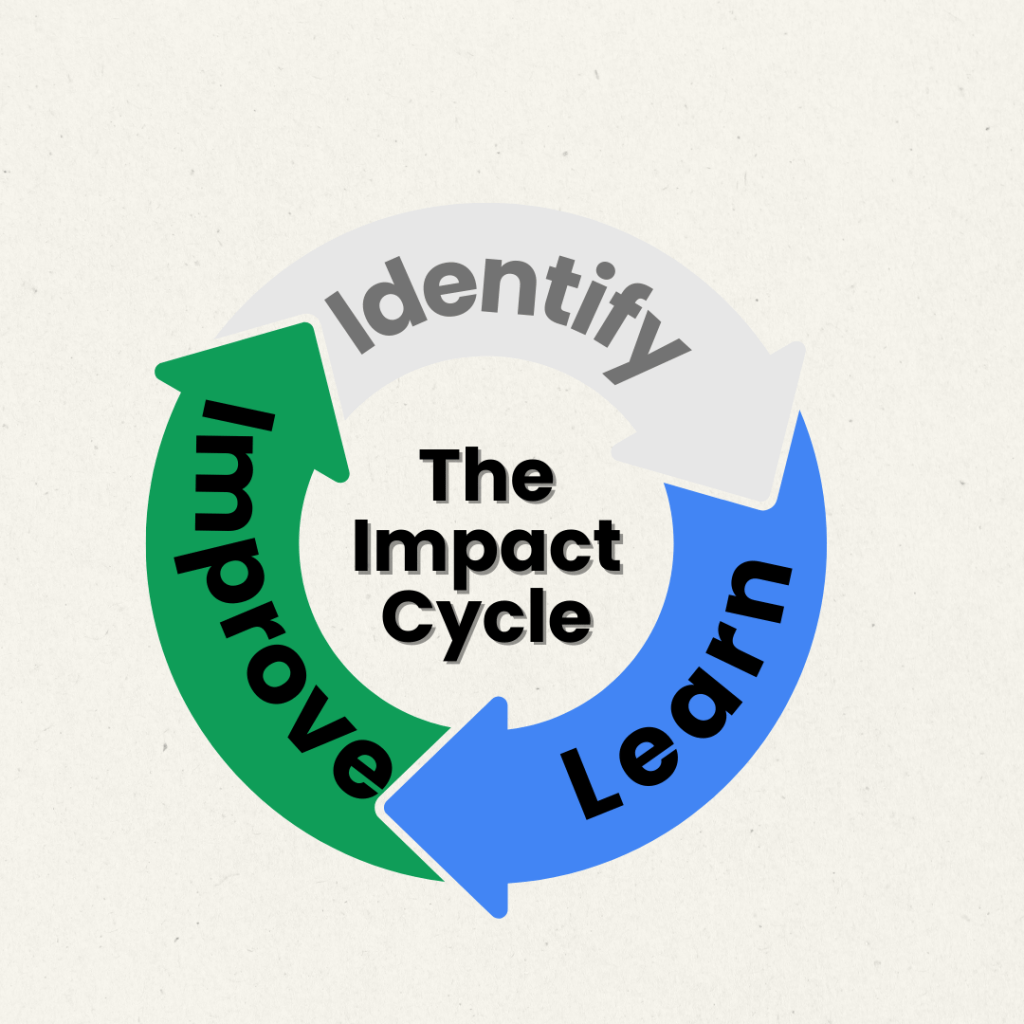

For my final project in ED 629: Survey of Instructional Technology Leadership, I delivered a presentation on Matt Miller’s (2023) AI for Educators: Learning Strategies, Teacher Efficiencies, and a Vision for an Artificial Intelligence Future. I later utilized this presentation in a professional learning session at my school in Spring 2024. At that time, the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in education was rapidly expanding, but many teachers in my district were hesitant, perceiving AI as a tool that students might use to cheat.

My presentation initiated important conversations across departments about how AI could enhance instruction by fostering student reflection and critical thinking. For instance, we explored incorporating AI chatbots into “think-pair-share” routines and using them to facilitate classroom debates. These activities demonstrated how AI can elevate instructional strategies by engaging students in deeper learning.

We also discussed how AI could support educators. Teachers expressed interest in using AI to personalize learning experiences tailored to students’ interests and to differentiate instruction. For example, we examined how AI could generate questions and prompts aligned with students’ current learning progressions.

The dialogue around AI integration continues at my school, and most teachers have begun gradually introducing AI tools. Our district recently adopted School AI, which allows educators to establish boundaries for student interactions with AI. The ability to specify what students can and cannot do with SchoolAI has addressed teachers’ initial concerns regarding students misusing AI. These ongoing professional learning experiences exemplify CETL Framework Skill 1E (Consortium for School Networking [CoSN], 2018), which emphasizes leveraging emerging technologies like AI to enhance education.

Wakelet Board

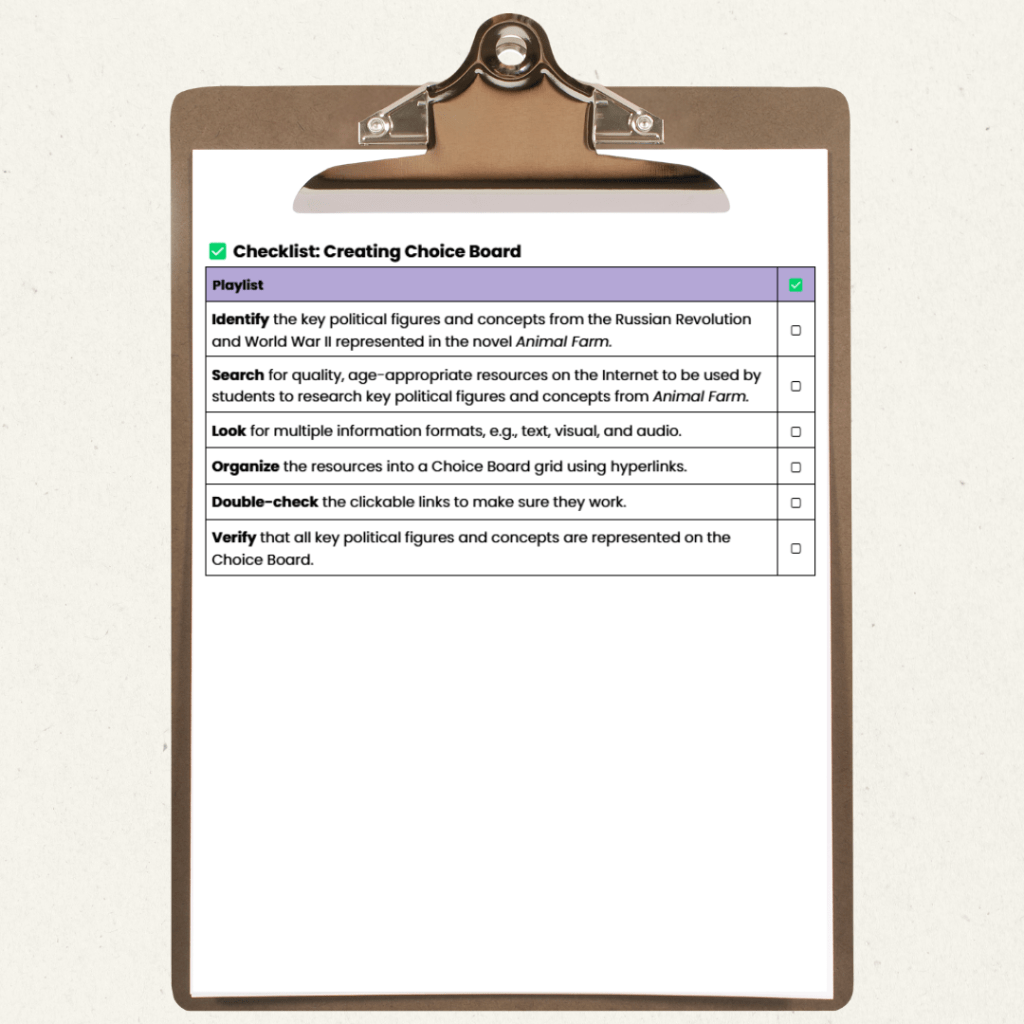

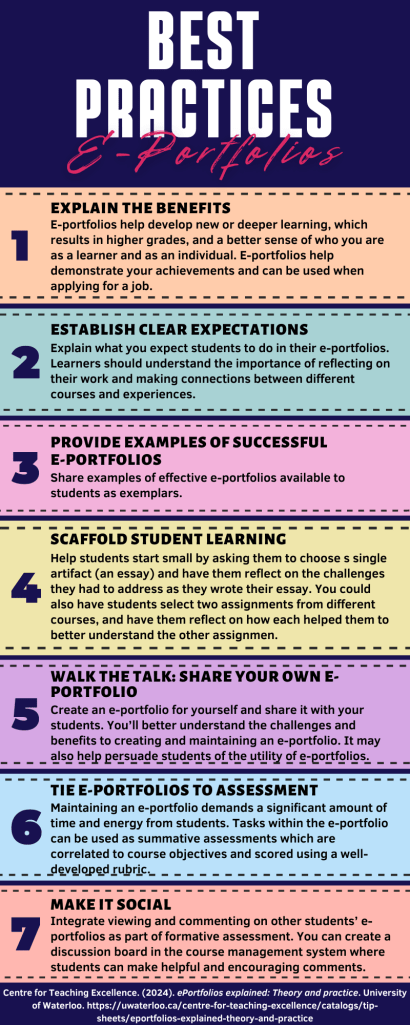

Wakelet, a digital communication tool, played a significant role in both ED 629: Survey of Instructional Technology Leadership and ED 601: Instructional Design and Development. In ED 629, I used Wakelet to organize and share resources with classmates, while in ED 601, I created a personal Wakelet collection for a getting-to-know-you activity (Wakelet Course Introductions). These experiences highlighted Wakelet’s versatility as a tool for curating resources, sharing information, and collaborating on projects.

I also saw Wakelet in action at the 2024 ALET Fall Conference, where presenters used it to share resources with attendees. Inspired by this, I incorporated Wakelet into my professional practice. For example, I created a Wakelet collection to curate resources for the PLC Book Study presentation described earlier and shared it with my teachers during a professional learning session (Wakelet PLC: AI for Educators). They appreciated how easily resources could be organized and accessed in one location.

This ability to communicate and collaborate using digital tools like Wakelet aligns with CETL Framework Skill 7B (CETL, 2018). Integrating Wakelet into my instructional practice enhanced my ability to efficiently connect educators with valuable resources.

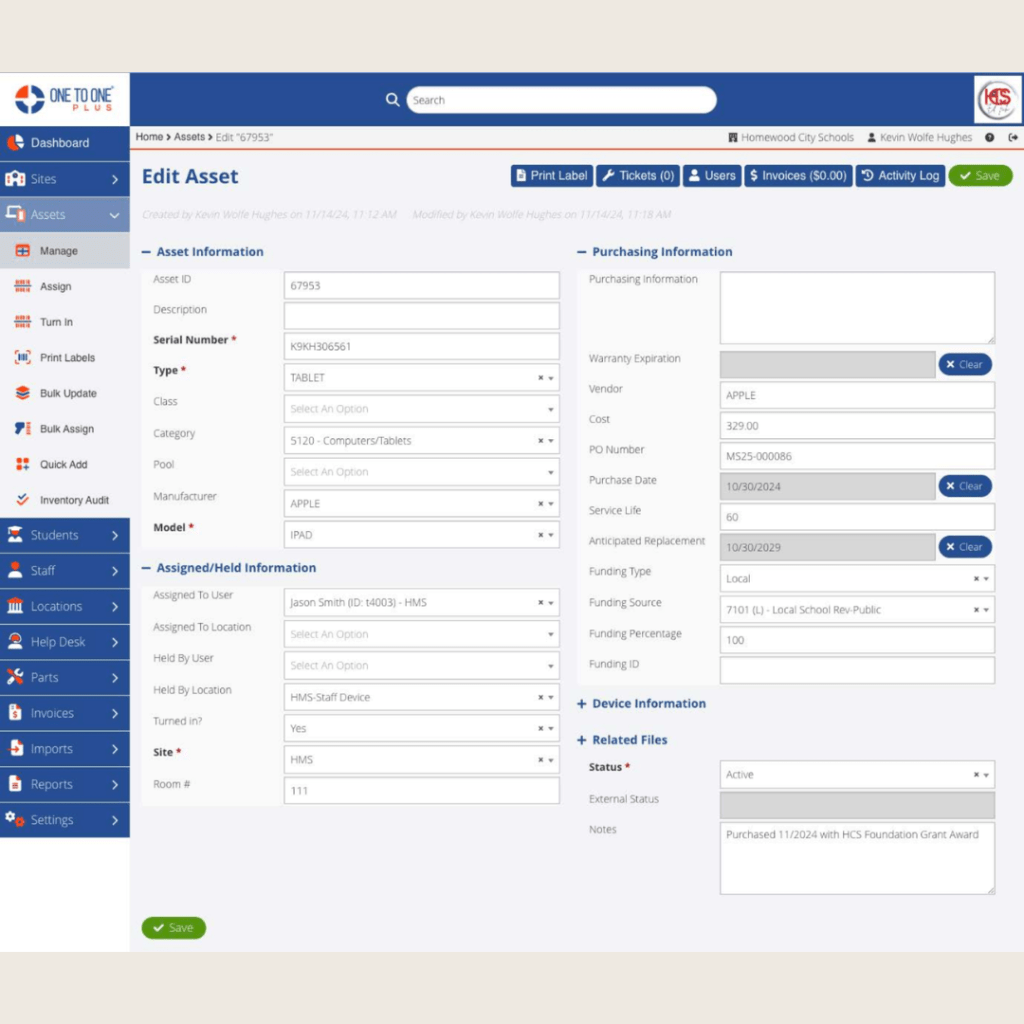

Data Management: OneToOne Plus

As an Instructional Technology Specialist, I manage the inventory of both technology and non-technology assets in my building. Recently, we implemented OneToOne Plus, a system for tracking and managing inventory. This platform allows me to enter new assets, update their status when they are lost or damaged, and ensure proper disposal when they expire.

Beyond maintaining accurate records, I conduct inventory audits, reconcile discrepancies, and present reports to the school board. These responsibilities require strong organizational and data management skills, directly aligning with CETL Framework Skill 9B (CETL, 2018), which focuses on managing data effectively.

Closing Thoughts

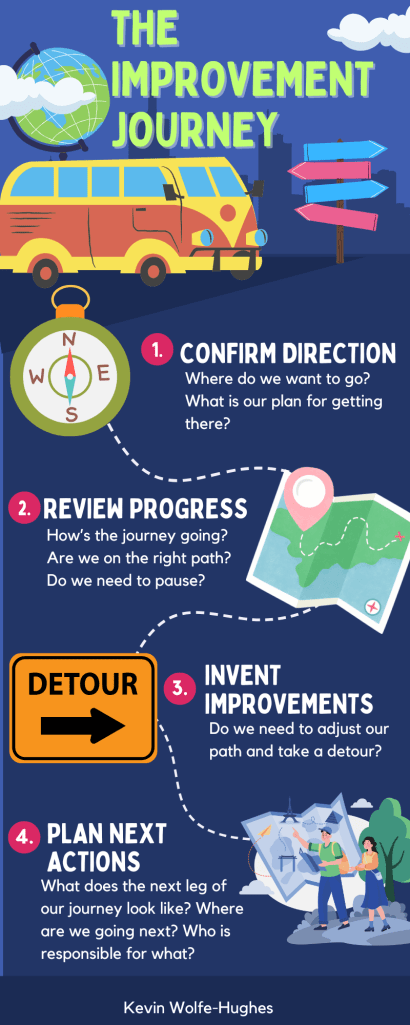

Completing my O-P-L record has been a transformative experience professionally. When I began the Ed.S. program, I had just transitioned from a classroom teacher to an Instructional Technology Specialist, a role requiring new skills closely aligned with the CETL Framework of Essential Skills. Reflecting on my progress through the O-P-L record has highlighted my growth and solidified my confidence as a technology leader in my district.

References

Consortium for School Networking. (2018). Framework of essential skills. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://www.cosn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Framework-December-2018.pdf

Miller, M. (2023). AI for educators: Learning strategies, teacher efficiencies, and a vision for an artificial intelligence future. Dave Burgess Consulting.