This last week I read Chapter 6 of Argument in the Real World by Turner and Hicks. This chapter focused on how users can interact with discussions on social media in a responsible way without spreading or sharing misinformation. With the widespread posting of misinformation via Internet platforms like social media, we must be vigilant in evaluating and questioning the validity of the information we encounter (Khan & Idris, 2019). Turner and Hicks (2011) offer the “MINDFUL heuristic” (p. 108) to help us do just that. MINDFUL helps us remember to always: MONITOR what we read and write; IDENTIFY the main claim of what we read or write; NOTE what evidence is used to support claims; DETERMINE if the evidence clearly supports the claim and what the mindset of the author is; FACTS – Identify if the evidence is based on facts, opinions, or both; UNDERSTAND opposing views to the argument; and LEVERAGE how others will take your response (Turner & Hicks, 2011, pp. 109-110).

The State Department of Education of California has recently undertaken the daunting task of rewriting the math framework for the state. Several prominent mathematicians have criticized the framework. Much of the criticism revolved around the citing of research that was not peer-reviewed in the document as well as some research that had opposite conclusions to what the framework document reports. The other big criticism is the introduction of new courses that would substitute for a second year of algebra. Many of these proposed courses are labeled as “data science,” when in reality they would be more appropriately named “data literacy.” Brian Conrad, a math professor and director of undergraduate studies in math at Sanford University, offers a helpful analogy to drive home his concern about these substitute courses for a second year of algebra. Conrad (2023) states “…much as music-appreciation courses won’t teach you how to play a piano, data literacy is not data science.”

Proponents of the new courses claim that the new courses will offer better outcomes for typically underrepresented groups in mathematics, for example, girls and students of color. Conrad argues that this will have the opposite effect by closing off access to careers in quantitative fields requiring the foundational knowledge and skills learned in Algebra II. The framework is misleading students and parents into believing that the substitute data science courses cover the same skills learned in Algebra II that will set students up for success in calculus in college. Without these skills, students may not be able to successfully navigate the quantitative courses at college that rely heavily on calculus.

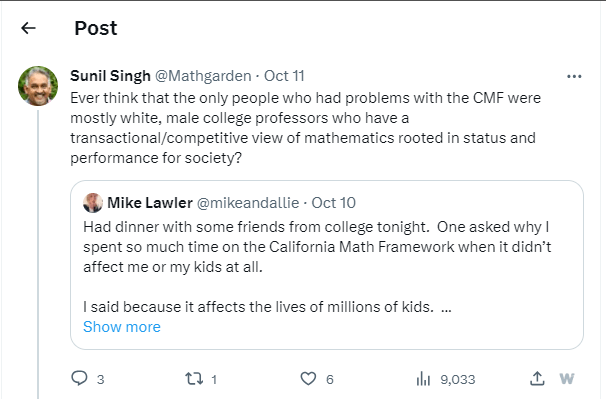

I chose a discussion that occurred on Twitter between Dr. Jelani Nelson, an Engineering and Computer Science professor at UC Berkeley, and Sunil Singh, a former mathematics and physics teacher (see below). Singh starts off the conversation with a claim that seems to criticize a post made by another person, Mike Lawler. Singh’s main claim – actually more of an opinion – is that the only people who take issue with the California Mathematics Framework (CMF) are white, male college professors who view math from a competitive perspective with only the prestigious being able to succeed in the field (Singh, 2023). Singh presents no evidence to support his claim. Lawler is a white, male and also a former math professor.

Dr. Nelson offers a rebuttal (see below) by stating that Singh is incorrect in his claim that the only people who have voiced concerns over the CMF are white, male college professors (Nelson, 2023). Dr. Nelson provides evidence in the form of a public open letter written by faculty members from 4-year colleges and universities across California. He provides a direct link to the open letter and also identifies professors who are not male or white. Dr. Nelson also offers another link to an Op-Ed piece written by two females to further support his counterclaim against Singh.

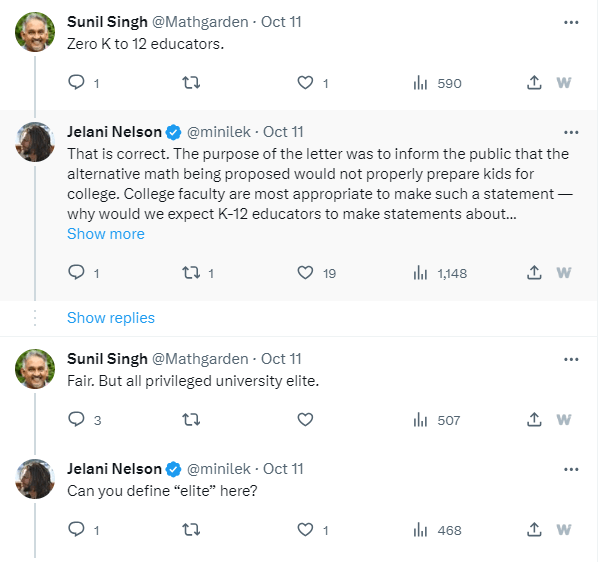

Singh responds to Dr. Nelson’s counterargument with the claim that there were no K-12 educators listed in the evidence presented (2023). This had nothing to do with his original claim that only white, male college professors took issue with the CMF. Dr. Nelson agreed with Singh about there being no K-12 educators involved in the open letter he presented as evidence. He follows that up with his own argument that the critique made in the open letter was that the new CMF does not prepare all students for college (Nelson, 2023). Dr. Nelson argues that college professors would be better judges of whether students will be prepared for college since they work at those colleges that future students will seek admission to. Singh responds to Nelson stating that the professors listed in the open letter are all “privileged university elite” (Singh, 2023). Again, this is more of Singh’s opinion and not supported by any evidence.

If Singh’s ultimate goal was to push out a narrative that a group of white, male professors are against the CMF as a way of keeping the status quo, he has not been very persuasive. His opinions are not backed up by any evidence to support his beliefs. On the other hand, Dr. Nelson does a great job of utilizing some of the digital writing skills outlined by Turner and Hicks (2011). Namely, Dr. Nelson’s claim was easy to understand. He offered evidence to support why Singh’s statement was incorrect in the form of hyperlinks that took the reader directly to the artifact and also served as a form of in-text citation.

The website housing the open letter has the names of eight faculty members from six different colleges and universities in California as well as the signatures of professors from other universities and colleges in the state. The signatories list their names, title, and the university/college with which they are affiliated. I found it easy to search and verify that these professionals were actually affiliated with these institutions and what their current roles were. With regard to the open letter itself, I liked that the authors used a Google Site to post the letter. Within the letter, hyperlinks were used to connect to the CMF document that was being critiqued. Other hyperlinks were used as a form of evidence to support the author’s concerns regarding the CMF document.

With the amount of information available on the Internet, users will eventually encounter biased and inaccurate information. Therefore, it is important that consumers of this information be able to “carefully filter, evaluate, and verify information to separate reliable content from wrong information” (Khan & Idris, 2019). Looking at the social media exchange I examined, it also requires the reader to be able to separate opinions from facts. With the way we consume information today, it is imperative that we all do our part to stop the spread of misinformation.

References

Conrad, B. (2023, October 2). California’s math misadventure is about to go national. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2023/10/california-math-framework-algebra/675509/

Khan, M. L., & Idris, I. K. (2019). Recognise misinformation and verify before sharing: A reasoned action and information literacy perspective. Behaviour & Information Technology, 38(12), 1194-1212. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1578828

Nelson, J. [@minilek]. (2023, October 11). This is incorrect. Perhaps the most significant pushback by university faculty is this letter: https://sites.google.com/view/mathindatamatters/home There are 8 authors: Moses [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/minilek/status/1712120663643971822

Nelson, J. [@minilek]. (2023, October 11). That is correct. The purpose of the letter was to inform the public that the alternative math being proposed would [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/minilek/status/1712120663643971822

Singh, S. [@Mathgarden]. (2023, October 11). Ever think that the only people who had problems with the CMF were mostly white, male college professors who have [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/minilek/status/1712120663643971822

Singh, S. [@Mathgarden]. (2023, October 11). Fair. But all privileged university elite [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/minilek/status/1712120663643971822

Singh, S. [@Mathgarden]. (2023, October 11). Zero K to 12 educators [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/minilek/status/1712120663643971822

Turner, K. H., & Hicks, T. (2017). Argument in the real world: Teaching adolescents to read and write digital texts.