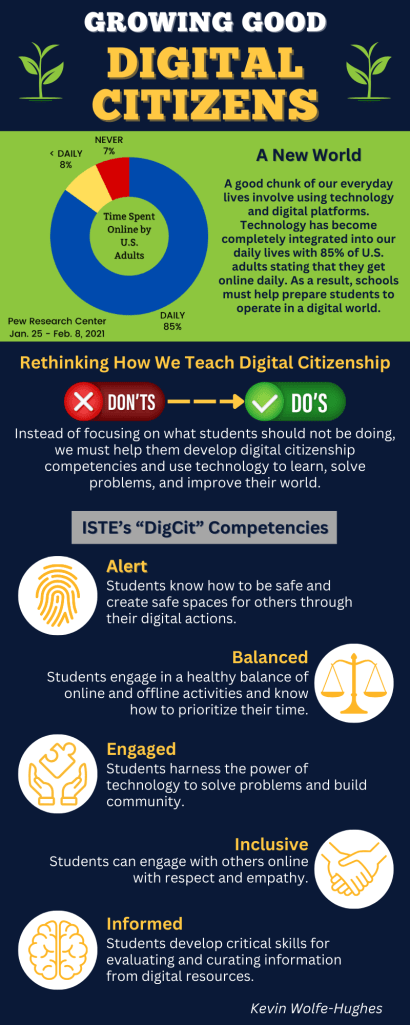

This Spring, I have been enrolled in a graduate course about digital leadership. For one of the modules, I created the infographic at the right. I shared the infographics with the teachers at my school to hopefully plant a seed for change. Too often our attempts at teaching digital citizenship end up being a list of “Don’ts” instead of guiding students to practice and develop the behaviors that exemplify a good digital citizen.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down in-person instruction at my school, the staff had started looking at incorporating the Alabama Digital Literacy Standards (Alabama State Department of Education [ALSDE], 2018) into each of our content areas. With the pivot to online instruction, this endeavor was placed on the back burner and soon forgotten. In my new role as the Instructional Tech Specialist at my school and as a result of this course, I believe now is a good time to start thinking about this again and how we can help our students become good digital citizens.

The Importance of Digital Citizenship

Öztürk (2021) defines digital citizenship “as the online display of behaviors that ensure legal, safe, ethical, and responsible use of information and communication technologies” (p. 33). The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) views digital citizenship as a concept that both teachers and leaders are responsible for teaching to students. This is such an important concept that ISTE has digital citizenship standards in place for instructional leaders, teachers, and students. Teachers are expected to “inspire students … to positively and responsibly participate in the digital world” (ISTE, 2019a, 2.3 Citizen section). Instructional leaders are expected to “model digital citizenship and support educators and students in recognizing the responsibilities and opportunities inherent in living in a digital world” (ISTE, 2019b, 4.7 Digital Citizen Advocate section). In addition to the ISTE standards, Alabama also has a “Citizens of a Digital Culture” (Alabama State Department of Education, 2018, p. 4) standard that recurs throughout grades K-12.

With the increased use of technology, our world is becoming more and more interconnected. This makes digital citizenship a global concern. With the increase in online learning, schools need to integrate digital citizenship across the curriculum to promote responsible and productive digital citizens (Capuno et al., 2022; Hamayel & Hawamdeh, 2022).

Digital Leaders and Digital Citizenship

Even though our current generation of students have grown up in a world heavily reliant on technology, that does not mean they know how to use technology effectively and responsibly. Many students “do not have a sense of the competencies to use it to support their learning or protect their identity” (Sheninger, 2019, p. 110). After reading Sheninger’s book, Digital Leadership, I feel that now is the time to start planning how my school can incorporate digital citizenship instruction into our curriculum.

I have decided to make this my summer project to engage in conversations with our Assistant Principal for Instruction about how we can plan to incorporate professional learning experiences throughout the school next year to help teachers incorporate digital citizenship into their courses. Based on Sheninger’s (2019) description of the Pillars of Digital Leadership, I have identified several pillars that will come into play as we plan.

Professional Learning & Growth – Much like Sheninger did with his teachers and students, I think it is important to create a professional learning community where everyone in the school shares what they are learning about digital citizenship and what questions they still have. This supportive and collaborative environment will help us to problem-solve and develop innovative ideas (Voogt et al., 2015).

Student Engagement & Learning – While there are plenty of online activities for teaching digital citizenship from sources like Google for Education and Common Sense Media, I think teachers will need to work together to adapt these activities for their specific subject areas and projects they are already using in their classrooms. Since digital citizenship encompasses problem-solving, information processing and creativity, content communication, and security (Hamayel & Hawamdeh, 2022), I am sure there are many existing activities that teachers are already using that can be tweaked to incorporate components of digital citizenship. By collaborating together through a professional learning community to adapt existing ideas or create new ones that align with the needs and realities of their students and community, teachers have ownership which increases their motivation and commitment to implementing their ideas effectively (Voogt et al., 2015).

Communication – To effect real change, we need to foster collaboration between our school, parents, and community to address the challenges and risks associated with technology use (Baydar, 2022). Many of the parents of our students are not digital natives and may not know how to discuss digital citizenship topics with their children. Inviting them to share in our journey will help encourage conversations about digital citizenship to continue outside of the school at home.

Closing Thoughts

I feel that the course I have completed on digital leadership has proven valuable in providing a frame of reference to help organize and plan the process of working with my colleagues to learn about digital citizenship together. From this collaboration, I am excited to see what wonderful ideas we will develop to enhance student learning. What started as the creation of a simple infographic has grown into a new opportunity for my school to grow and empower our students to become good digital citizens.

References

Alabama State Department of Education. (2018). Alabama course of study: Digital literacy and computer science. https://www.alabamaachieves.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AS-2018-Digital-Literacy-and-Computer-Science-COS.pdf

Baydar, F. (2022). The role of educational leaders in the development of students’ technology use and digital citizenship. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Technology, 10(1), 32-46. https://doi.org/10.52380/mojet.2022.10.1.367

Capuno, R., Suson, R., Suladay, D., Arnaiz, V., Villarin, I. & Jungoy, E. (2022). Digital citizenship in education and its implication. World Journal on Educational Technology: Current Issues, 14(2), 426-437. https://doi.org/10.18844/wjet.v14i2.6952

Hamayel, H. J., & Hawamdeh, M. M. (2022). Methods used in digital citizenship: A systematic literature review. Journal of Digital Educational Technology, 2(3), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.30935/jdet/12520

International Society for Technology in Education. (2019a). ISTE standards: For educators. https://iste.org/standards/educators

International Society for Technology in Education. (2019b). ISTE standards: For coaches. https://iste.org/standards/coaches

Öztürk, G. (2021). Digital citizenship and its teaching: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology & Online Learning, 4(1), 31-45.

Sheninger, E. (2019). Digital leadership: Changing paradigms for changing times (2nd ed.). Corwin; International Center for Leadership in Education.

Voogt, J., Laferrière, T., Breuleux, A., Itow, R. C., Hickey, D. T., & McKenney, S. (2015). Collaborative design as a form of professional development. Instructional Science, 43(2), 259–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-014-9340-7