In my graduate class on distance learning, we examined continuity of instruction. As a starting point for my exploration, I looked at the Continuous Learning Rubric v2.1 (ClassLink et al., n.d.). Three elements from this document resonated with me as an Instructional Tech Specialist: instructional delivery method, professional development, and communication. I chose these three elements because they were areas that I could focus on with our Assistant Principal for Curriculum and Instruction to help support our students, parents, and faculty.

Instructional Delivery Method

An instructional delivery method is described as an outline of the instructional delivery methods for various scenarios (ClassLink et al., n.d.). At my school, I train the teachers on using Schoology, our Learning Management System (LMS). One thing we could do is utilize Schoology to help ensure the continuity of instruction is maintained with respect to teacher absences and school closures. Miami-Dade County Public Schools (2023) have a well-designed plan for teacher absences and school closures. Their plan for teacher absences covers two scenarios: planned and unplanned absences. If an absence is planned in advance, the district has teachers post the lesson on Schoology so that it can be completed asynchronously in class. The substitute teacher directs students to access Schoology and begin work on the lesson.

For unplanned absences, the district has teachers create a folder labeled “Emergency Lesson Plans” in Schoology at the beginning of the school year. The folder is left unpublished for students. Teachers are expected to routinely update the emergency lessons in this folder so the plans remain current with where students are in the course. When a teacher calls in an unplanned absence, the LMS manager accesses the teacher’s Schoology classes and publishes the lesson plan. Again, the substitute teacher would simply direct students to access Schoology and begin work on the lesson.

In the event of school closures, Miami-Dade County Public Schools (2023) follows a similar procedure: Teachers place asynchronous work in Schoology for students to complete. The Miami-Dade policy directs teachers to be flexible with deadlines for work to be completed when there is bad weather, which could affect access to power and Internet service. We have a similar procedure at my school for e-Learning days during emergency school closures. Unfortunately, these are stand-alone lessons that may or may not be related to the content students are currently covering in class. In order to maintain continuity in the course, the lessons should really reflect what the students are currently covering in class.

My school does not use Schoology like Miami-Dade does when teachers are absent. I think it’s important to revise our existing policies to improve how we promote the continuity of learning in our school based on Simonson and Zvacek (2024), who emphasize the importance of revising institutional policies to assess readiness for distance education. Students and parents need opportunities to practice utilizing Schoology to complete online lessons so that they know how to function online. This is important considering how unprepared students, parents, and teachers were to switch to online learning during the pandemic.

Professional Development

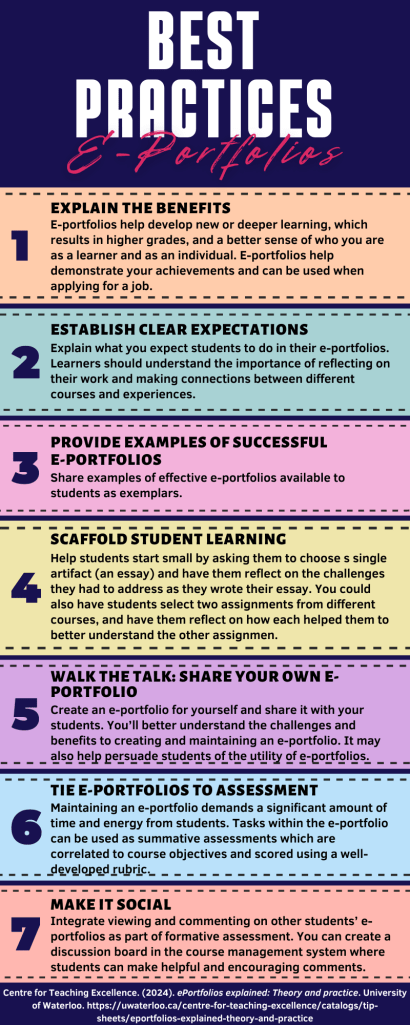

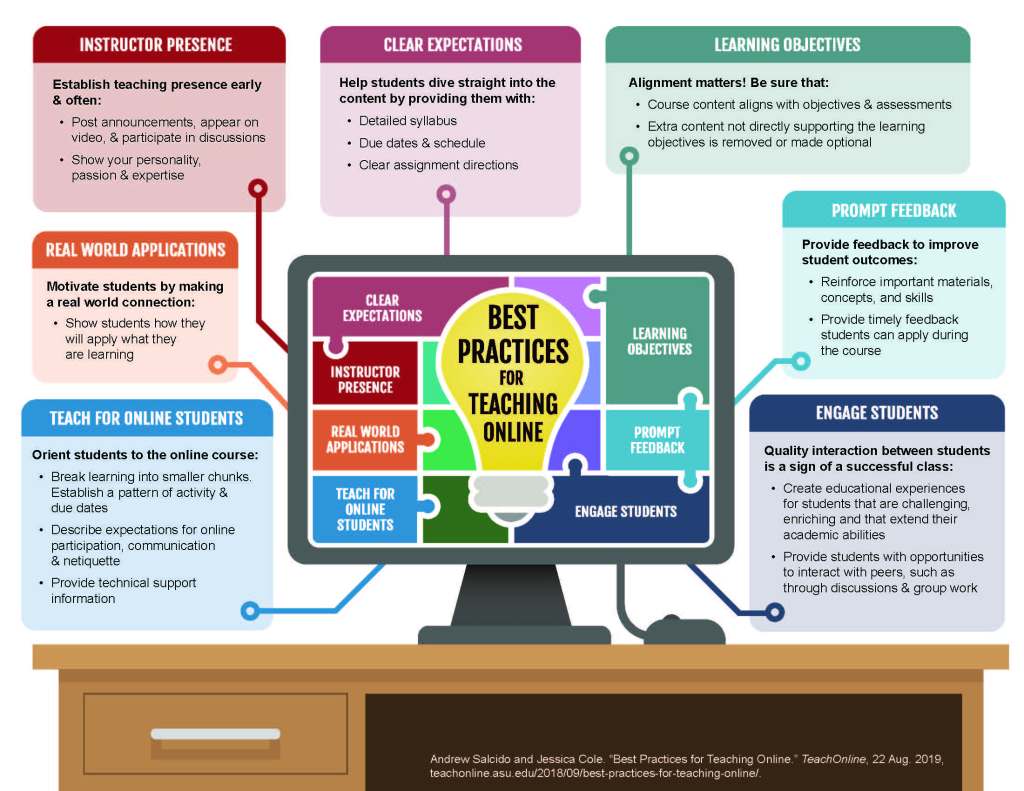

If teachers are expected to incorporate opportunities for distance learning within Schoology to maintain the continuity of learning, it is important that they are trained to do so. Teachers need training on the tools the district has chosen for instruction and support for developing the pedagogical skills needed when teaching remotely (ClassLink et al., n.d.). Simonson and Zvacek also stress that “appropriate faculty training is an absolutely imperative readiness concern” (2024, p. 308). While we do provide teachers with ongoing professional learning opportunities for face-to-face classroom instruction, I think it is worthwhile to incorporate best practices in teaching online. Utilizing the embedded planning time in our school schedule, teachers within the same content area can work together to plan online lessons with the same level of academic rigor as face-to-face instruction (Simonson & Zvacek, 2024).

Teachers will likely need the most help ensuring their online materials are accessible. This involves considering the limitations of the LMS and related applications, ensuring software compatibility with assistive devices, and aligning resources with WCAG 2.2 standards (Simonson & Zvacek, 2024). We must ensure that all students, including those with Individualized Education Plans or 504 Plans, can also access and interact with the lessons teachers post online. This will require the expertise of special education teachers in the planning and review process.

Communication

Schools should continuously communicate with all stakeholders about operations, policies, and instruction (ClassLink et al., n.d.). Part of my job at my school is to maintain the school’s website. Currently, we do not have any information on the website about our continuity plan. In researching this topic, I discovered the Miami-Dade County Public Schools Continuity Plan (2024) posted on their website. One of the features I like about their site is that it houses all of the information in one location. Stakeholders can find information regarding the Instructional Continuity Plan, school devices, the district’s LMS, support documents, self-help videos, and contact information for live support. Communication is key in supporting both students and parents to successfully navigate and participate in online learning opportunities (Simonson & Zvacek, 2024).

With my district moving to a 1:1 device model this year, students and parents will need access to information about how to use the school device they will be issued. Providing parents with information on Schoology and how they can create a parent account to support their student’s learning would also be beneficial since middle school is the first time that Schoology is used extensively across all classes. For many parents (and students), I think it would be helpful to offer in-person training on how to get the most out of Schoology. By communicating this information with parents and students, I believe that we can all work together to support our students when they have to participate in online learning.

Closing Thoughts

I’m currently writing this post during the summer. The teachers are enjoying their break, and I’m using this time to prepare for the upcoming 2024-2025 school year. It’s an ideal time to collaborate with my building administrators and start thinking about professional learning opportunities to help our teachers develop the pedagogical skills to develop effective online lessons that can be used with our students. By providing online learning opportunities to our students, they will develop the skills to be successful in their online assignments. This will help to ensure that we are prepared to continue learning no matter what disruptions may occur.

References

ClassLink, American Association of School Administrators, Association of Educational Service Agencies, Consortium for School Networking, & State Educational Technology Directors Association. (n.d.). Continuous learning rubric v2.1. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1lXAwsLWBfNslkhIGxHqgojVjmV5n8KIrR7SCmZnNqsA/edit?gid=1000901060#gid=1000901060

Miami-Dade County Public Schools. (2024). M-DCPS instructional continuity plan. Retrieved June 22, 2024, from https://icp.dadeschools.net/#!/fullWidth/7271

Miami-Dade County Public Schools. (2023). Best practices to ensure the continuity of instruction. Innovation and School Choice. Retrieved June 22, 2024, from https://innovationschoolchoice.com/instructional-continuity/

Simonson, M., & Zvacek, S. (2024). Teaching and learning at a distance: Foundations of distance education (8th ed.). Information Age Publishing, Inc.

W3C Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI). (4, December 2017). Introduction to web accessibility and W3C standards [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/20SHvU2PKsM

World Wide Web Consortium. (2024). WCAG 2 overview. W3C Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI). Retrieved June 22, 2024, from https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/