Recently, I found myself engaged in a discussion with some colleagues regarding security and ensuring that district and federal policies were being followed regarding student privacy and the security of student data. The teachers did not understand why they could not use a free digital resource with their students. This particular resource allowed users to utilize single sign-on with their school-issued Google accounts. The teachers’ thinking was that it was safe to use this resource because it was free and students did not have to create an account on the website.

This conversation was very informative to me. While most teachers are aware of the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), their view of privacy protection seems to be lacking a digital lens. As an Instructional Tech Specialist, I provide leadership in the area of student engagement and learning. This is one of the Pillars of Digital Leadership described by Sheninger (2019). Sheninger also describes this leadership role as being influenced by the Future Ready Framework–the Data and Privacy area in particular.

Privacy Laws

Two main federal laws regulate the privacy and security of student data: the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA).

Importance of Vetting Resources

Even with these laws in place, there are still issues with vendors not being completely transparent with their privacy policies or disregarding the requirements outlined in COPPA altogether (Frazier & Hearrington, 2024). For example, vendors who offer free services often share collected data with third parties to make money. These third parties can use this data to develop profiles of children and build behavioral ads targeting these children.

When viewed from the Data and Privacy area of the Future Ready Framework (All4Ed, 2024), technology leaders must ensure that procedures are in place to vet all digital resources to verify their educational value and security. When it comes to educational value, the resource should be judged on its ability to help teachers and students achieve learning targets. The content should also be developmentally appropriate for the intended age group. Considering security, the vendor of the resource “should encrypt user data to provide a basic assurance of security, especially products housing student data” (Zimmerle, 2021). As mentioned above, federal laws require that vendors clearly state within their privacy policies what data is collected from students and how that data is used. This is where the issue with free resources comes into play. Many free resources actually make money from selling or sharing student data. Often this data is used to create contextual or targeted advertising (Kelly, Graham, & Garton, 2023; Zimmerle, 2021).

Privacy Information Resources

Common Sense has a Privacy Program that evaluates the privacy policies of popular products to help schools and parents make informed decisions about the tools their students are using. Privacy evaluations are provided for a range of apps along with explanations of the ratings. Common Sense also provides access to publications, written by privacy law experts, that share information on important issues surrounding digital citizenship and student learning.

One such publication, the 2023 Privacy Program Evaluation Framework (Kelly, Graham, & Garton, 2023), assesses products using “multiple dimensions of privacy, safety, security, and compliance, incorporating criteria based on legal, societal, educational, and child development practices” (Common Sense Media, n.d.). The appendix of this report is extremely useful. When evaluating a product based on a specific component of law, the links in the appendix navigate to the questions that should be considered in the evaluation process.

Vetting Recommendations

Zimmerle (2021) recommends educating teachers on the law and why vetting is so important especially when it comes to free resources. Even if teachers have been trained on the importance of security and privacy of student data, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) states that it is best practice for school districts to vet online resources instead of leaving it up to teachers (2020, July).

When vetting resources, Student Privacy Compass, formerly known as FERPA|Sherpa, suggests asking the following ten questions (Gallagher, Magid, & Pruitt, 2021, p. 9 ).

- Does the product collect PII?

- Does the vendor commit not to share student information other than as needed to provide the educational product or service? The vendor should clearly promise never to sell data.

- Does the vendor create a profile of students, other than for the educational purposes specified?

- When you cancel the account or delete the app, will the vendor delete all student data that has been provided or created?

- Does the product show advertisements to students? Behaviorally targeted advertising is never acceptable for school use.

- Does the vendor allow parents to access data it holds about students or enable schools to access data so the school can provide the data to parents in compliance with FERPA?

- Does the vendor promise to provide security for the data it collects? Look for products that use encryption when storing and transmitting student data.

- Does the vendor claim it can change its privacy policy without notice at any time? The FTC requires vendors to provide notice to users when their privacy policies change and get new consent for the collection and use of their data.

- Does the vendor say that if the company is sold, all bets are off? The policy should state that any sale or merger will require the new company to adhere to the same protections.

- Do reviews or articles about the product or vendor raise any red flags?

Closing Thoughts

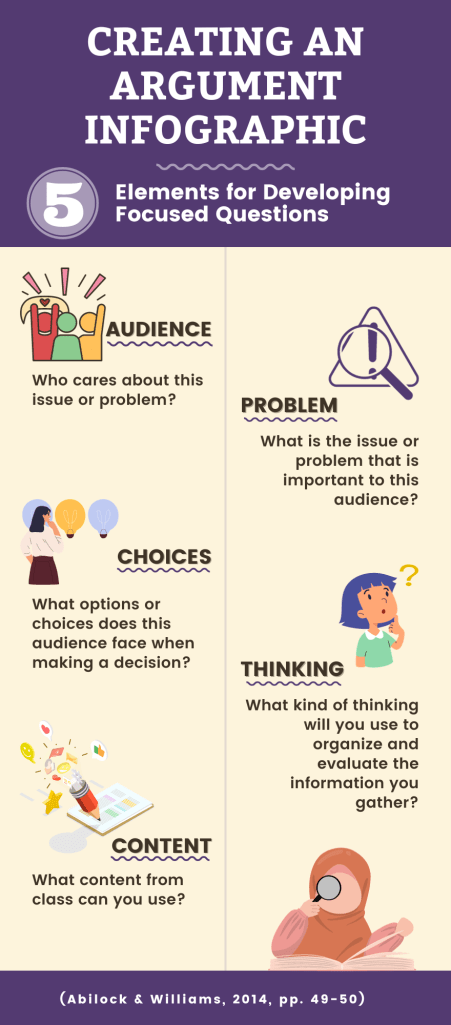

Thinking back to Sheninger’s (2019) description of the roles and qualities of an effective digital leader, I examined how I might be a more effective leader with regard to helping teachers understand the importance of Data and Privacy. With this in mind, I have redesigned my training with teachers to incorporate more of the information about the law and good practices I discovered in my research here. Before teachers request permission from the district to utilize new digital resources, they will now be able to examine these resources from a Data and Privacy perspective.

References

Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998, 15 U.S.C. §6501 et seq. (1998). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2022-title15/pdf/USCODE-2022-title15-chap91-sec6501.pdf

Common Sense Media. (n.d.). Common sense privacy program: Publications. Retrieved from https://privacy.commonsense.org/resource/publications

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974, 20 U.S.C. § 1232g et seq. (1974). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2022-title20/pdf/USCODE-2022-title20-chap31-subchapIII-part4-sec1232g.pdf

Federal Trade Commission. (2020, July). Complying with COPPA: Frequently asked questions. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/complying-coppa-frequently-asked-questions

Frazier, M., & Hearrington, D. (2024). The technology coordinator’s handbook (4th ed.). International Society for Technology in Education.

Gallagher, K., Magid, L., & Pruitt, K. (2021). The educator’s guide to student data privacy. Student Privacy Compass. Retrieved from https://studentprivacycompass.org/audiences/educators/

Kelly, G., Graham, J., & Garton, S. (2023). 2023 Privacy Program Evaluation Framework. Common Sense Media.

Sheninger, E. (2019). Digital leadership: Changing paradigms for changing times (2nd ed.). Corwin; International Center for Leadership in Education.

Student Privacy Compass (2020, August 13). Adopting EdTech: Privacy vetting [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lU8v1orttis&t=629s

Student Privacy Compass (2024). Welcome to student privacy compass. https://studentprivacycompass.org/