As part of my ED 601 course on Instructional Design and Development, I have been using the ADDIE Model to develop a training session for the teachers at my school. I am currently in the Design phase of this process, which includes determining the strategies I might use in the training. For this reflection, I am focusing on two strategies: assessing prior knowledge and incorporating multimedia instruction. In this post, I will discuss how these strategies foster learning and provide guidelines for using them. I will also share examples of each strategy.

Assessing Prior Knowledge: Pre-Assessment

According to Brown and Green (2024), identifying prior knowledge of a topic or skill is a critical component of understanding learners and designing effective instruction. Prior knowledge can be identified in several ways, including pre-assessments, concept maps, K-W-L charts, probing questions, and formative assessments. Since my training session focuses on using the basic features of a Chromebook and troubleshooting common issues, I believe a short pre-assessment will help me determine how familiar teachers are with these features. This pre-assessment can be administered electronically before the training session.

Pre-assessments benefit both instructors and learners. Studies have shown that pre-assessing not only provides feedback to instructors about learners’ understanding but also serves as a “metacognitive ‘reality check’—highlighting the gaps in one’s knowledge and facilitating a search for relevant information during subsequent study” (Pan et al., 2020, p. 544). Guskey and McTighe (2016) outline six benefits of using pre-assessment as part of instruction:

- Identifying learners’ prior knowledge and skills

- Monitoring student progress by providing baseline data

- Communicating expectations about what will be learned

- Focusing learners’ attention on learning targets rather than the activities they will engage in

- Checking for preconceived ideas or misunderstandings so they can be addressed directly during instruction

- Identifying learners’ interests, talents, and preferred ways of learning

Guskey and McTighe (2016) also provide three guidelines for the effective use of pre-assessments. First, it is important to clarify the purposes of pre-assessment. From a design perspective, determine why you are pre-assessing, what data you intend to uncover, and how you will collect the information. It is also crucial to communicate to learners that the pre-assessment is intended to help address their needs and will not be used for grading purposes. Second, use the pre-assessment data to take action: review skills or knowledge that may be lacking, address misconceptions, provide targeted instruction, or differentiate instruction. Finally, be careful not to overuse pre-assessments. They are most useful when they provide information you do not already have or cannot anticipate in advance. When used, pre-assessments should be brief, easy to administer, and easy to interpret.

Here is an example of a pre- and post-assessment I used when I taught algebra: Unit 7 “I Can…” Statements. I found this was a low-stress and easy way for my students to let me know what they felt like they knew or did not know. My students appreciated the check lists because the lists helped them identify areas they needed to focus on when preparing for their summative assessments.

Multimedia Instruction

Multimedia instruction focuses on lessons that incorporate “words (such as spoken or printed text) and pictures (such as illustrations, graphs, maps, photos, animations, or videos)” (Mayer, 2008, p. 760). According to Brown and Green (2024), the visual display of information plays an important part in effectively communicating information so that it is easy for learners to understand and process. It follows then that instructional designers need to know basic visual design principles as well as principles for designing effective multimedia instruction. Even if some work is completed by a commercial artist, the instructional designer must ensure that the final project helps the learner understand the content.

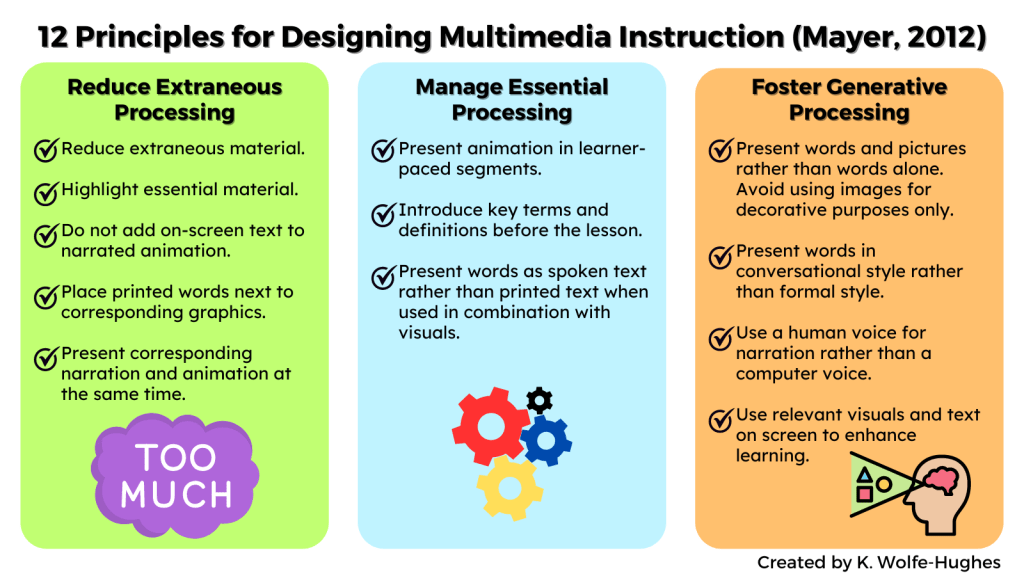

Through his research, Mayer (2012) developed twelve principles for designing effective multimedia instruction. These principles are based on three assumptions about learners: (1) they use two distinct channels for processing visual and auditory information, (2) they have a limited capacity for processing information, and (3) they must be actively engaged in the learning process. The twelve principles are categorized into three areas: reducing extraneous processing, managing essential processing, and fostering generative processing. The graphic below illustrates these three areas and the twelve principles.

The Digital Learning Institute (2024) has a blog post that provides more specific information about the twelve principles for designing multimedia instruction, along with examples of each principle. Some of these principles overlap with basic visual design principles. I have encountered some of these principles when completing online training modules. In particular, I find the segmenting principle beneficial as a learner. Rather than being presented with a continuous stream of information, I have an easier time processing and understanding the material when it is broken into more manageable pieces. I also feel that I have more agency when I can control when I am ready to move on to the next piece of information.

Final Thoughts

When considering the Design phase of the ADDIE model, I have gained a deeper appreciation for the importance of keeping the learner in mind. This involves using information about learners’ prior knowledge and preconceived ideas to design instruction that meets their specific needs, which may vary from group to group. Equally important is considering how information is presented to learners. Most of the training I conduct with teachers involves technology, which requires demonstrating how to use it. To do this effectively, I combine visuals and words. Keeping Mayer’s twelve principles for multimedia instruction in mind will help me present information in a way that fosters learner engagement and facilitates efficient processing.

References

Brown, A. H., & Green, T. D. (2024). Essentials of instructional design: Connecting fundamental principles with process and practice (5th ed.). Routledge.

Digital Learning Institute. (2024). Mayer’s 12 principles of multimedia learning. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.digitallearninginstitute.com/blog/mayers-principles-multimedia-learning

Guskey, T. R., & McTighe, J. (2016). Pre-assessment: Promises and cautions. Educational Leadership, 73(7), 38–43.

Mayer, R. E. (2008). Applying the science of learning: Evidence-based principles for the design of multimedia instruction. American Psychologist, 63(8), 760-769.

Mayer, R. E. (2012). Multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Pan, S. C., Schmitt, A. G., Bjork, E. L., & Sana, F. (2020). Pretesting reduces mind wandering and enhances learning during online lectures. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9(4), 542-554.

Tucker, C. (2024, March 4). Using pre-assessment data to design more effectively [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LvaTgjHF50E